Bells have tolled in Hiroshima, Japan, to mark the 75th anniversary of the dropping of the world’s first atomic bomb.

But memorial events were scaled back this year because of the pandemic.

It has become emotionally scarred what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this horror and trauma will forever live in the history of Japan, they have accepted to live with it, knowing that this is the only way to accept what has already happened.

On 6 August 1945, a US bomber dropped the uranium bomb above the city, killing around 140,000 people.

Three days later a second nuclear weapon was dropped on Nagasaki. Two weeks later Japan surrendered, ending World War Two.

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the mayor of Hiroshima joined bomb survivors and descendants in the city’s Peace Park.

The park is usually packed with thousands of people for the anniversary, But attendance was significantly reduced this year, with chairs spaced apart and most attendees wearing masks.

A moment’s silence was held at 08:15, the exact time the bomb was dropped on the city.

“On August 6, 1945, a single atomic bomb destroyed our city. Rumour at the time had it that ‘nothing will grow here for 75 years,'” Mayor Kazumi Matsui said. “And yet, Hiroshima recovered, becoming a symbol of peace.”

The day Michiko nearly missed her train

Women survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs

In a video message, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres called on all nations to renew efforts to abolish such weapons.

“Division, distrust and a lack of dialogue threaten to return the world to unrestrained strategic nuclear competition,” he said. “The only way to totally eliminate nuclear risk is to totally eliminate nuclear weapons.”

A train journey that saved a life

On the morning of 6 August 1945, Michiko overslept.

“I ran to Yokogawa station, and I jumped on my usual train in the nick of time,” she wrote in her diary years later.

Michiko’s sprint saved her life. It meant she was safely inside her workplace when her city – Hiroshima – was hit by the first nuclear bomb ever used in war.

“If I had missed my usual train, I would have died somewhere between Yokogawa station and Hiroshima station.”

The United States believed that dropping a nuclear bomb – after Tokyo rejected an earlier ultimatum for peace – would force a quick surrender without risking US casualties on the ground.

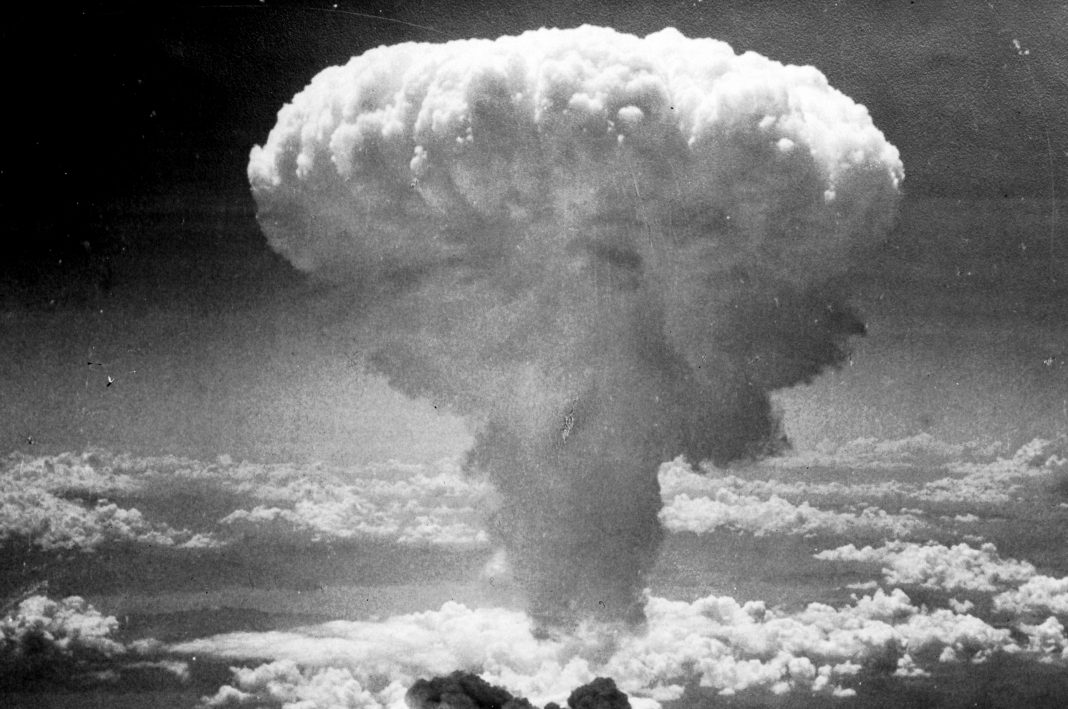

On 6 August, the US dropped the first bomb – codenamed Little Boy – on Hiroshima. The attack was the first time a nuclear weapon was used during a war.

At least 70,000 people are believed to have been killed immediately in the massive blast which flattened the city. Tens of thousands more died of injuries caused by radiation poisoning in the following days, weeks and months.

When no immediate surrender came from the Japanese, another bomb, dubbed “Fat Man”, was dropped three days later about 420 kilometres (261 miles) to the south over Nagasaki.

The recorded death tolls are estimates, but it is thought that about 140,000 of Hiroshima’s 350,000 population were killed, and that at least 74,000 people died in Nagasaki.

They are the only two nuclear bombs ever to have been deployed outside testing. The dual bombings brought about an abrupt end to the war in Asia, with Japan surrendering to the Allies on 14 August 1945.

But some critics have said that Japan had already been on the brink of surrender and that the bombs killed a disproportionate number of civilians.

Japan’s wartime experience has led to a strong pacifist movement in the country. At the annual Hiroshima anniversary, the government usually reconfirms its commitment to a nuclear-free world.

After the war, Hiroshima tried to reinvent itself as a City of Peace and continues to promote nuclear disarmament around the world.

Seventy-five years after the Enola Gay opened its bomb bay doors, 31,000ft above Hiroshima, views on what happened that day are still deeply polarised.

Those on the ground who lived to tell the tale see themselves, understandably, as victims of an appalling crime. Sitting and talking with any “hibakusha” (survivor) is a deeply moving experience. The horrors they witnessed are almost unimaginable. Hordes of zombie like people, their skin melted and hanging in ribbons from their arms and faces; mournful cries from the thousands trapped in the tangle of collapsed and burning buildings; the smell of burned flesh. Later came the black rain and the agonising deaths from a strange new killer – radiation sickness.

But any visitor to the Hiroshima Peace Museum might justifiably ask, where is the context? After all, the atom bombs didn’t come out of nowhere. You’ll find scant mention of the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, let alone the horrors of the Nanjing Massacre, or the slaughter at Peleliu, Manila, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. And so, to many Japanese, Hiroshima and Nagasaki stand oddly alone, detached from the rest of history, symbols of the unique victimhood of Japan, the only country ever to experience a nuclear attack.

The lack of context can feel equally egregious on the other side. When I last visited Hiroshima, I asked a group of visiting American college students what they had learned in school about the attack. One young man summed it up like this: “America embarked on a tremendous scientific effort. The result was that in a flash the war was over.” The idea that Hiroshima ended the war in a single stroke is comforting, but it leaves out the second attack on Nagasaki and quite a lot else.

Before “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima, more than 60 other Japanese cities had already been destroyed by American fire bombing. The largest death toll from a single attack (in any war) is not Hiroshima, but the fire-bombing of Tokyo in March 1945. The attack created a fire storm which took 105,000 civilian lives. That ugly record stands to this day. Then there is the little-known fact that several more atom bombs were being prepared for shipment to Tinian Island. If Japan had not surrendered on 15 August, the US air force was prepared to keep dropping atom bombs until it did.

The bomb that changed the world

The bomb was nicknamed “Little Boy” and was thought to have the explosive force of 20,000 tonnes of TNT

Col Paul Tibbets, a 30-year-old colonel from Illinois, led the mission to drop the atomic bomb

The Enola Gay, the plane which dropped the bomb, was named in tribute to Col Tibbets’ mother.

The final target was decided less than an hour before the bomb was dropped. Good weather conditions over Hiroshima sealed the city’s fate

On detonation, the temperature at the burst-point of the bomb was several million degrees

The blast generated a vast shockwave which flattened buildings

Thousands of people on the ground were killed or injured instantly.